THE LEGACY OF THE CANTATA

Interview with Felipe Izcaray

By Gorgias Sánchez (Caracas, June 18, 2018)

Maestro Felipe Izcaray, renowned Venezuelan choral and orchestral conductor currently residing in Venezuela, directed a Latin American program in its entirety in April 2018 in Colombia, which included the "Cantata Criolla" by Venezuelan composer Antonio Estévez . This was the first time the work had been heard in Colombian territory and it was performed with the National Symphony Orchestra of Colombia, the Universidad de los Andes Symphonic Choir and the Javeriano Chamber Choir. On this occasion the soloists were the Venezuelans Cristo Vassilaco (tenor) and Juan Tomás Martínez (baritone). Thirty-one years ago, in 1987, Maestro Izcaray had his first encounter on the podium with this magnificent work, perhaps the most representative of twentieth-century Venezuelan nationalism. On that occasion he had the privilege of having the composer's own tutelage and of having the Caracas Municipal Symphony Orchestra at his disposal. It was the first time that the "Cantata Criolla" would not be conducted by its creator, Maestro Antonio Estévez, and also the first time that it had not been conducted with the Venezuela Symphony Orchestra, an institution that financed the 1st Vicente Emilio Sojo Composition Contest in the year 1954, where Estévez won the 1st prize with this work. It was the first time the legacy had been passed down.

A year later, in 1988, Antonio Estévez would pass away, leaving us this wonderful Cantata as a seal of our Venezuelan identity. Fortunately, he left the baton in the hands of Maestro Felipe Izcaray, who unquestionably stands as the legatee of the “Cantata Criolla”.

________________

Maestro Felipe, we are aware that despite the fact that Venezuela and Colombia share much of their culture in common, especially across the plains, there are marked differences that could be interesting to highlight when contrasting the carrying out montage here or there. What could you tell us about your last experience with the “Cantata Criolla” in Colombia this past April?

It was an unforgettable experience, full of positive and very emotional experiences. I take this opportunity to thank the National Symphony Orchestra of Colombia and its principal conductor, Maestro Olivier Grangean, for the invitation to conduct what I consider to be a historic concert within the framework of Colombian-Venezuelan cultural identity.

Is this the first time that you perform this piece outside Venezuela?

Yes and no. In 1995 I conducted the work on the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra tour to France with Venezuelan and French choirs. The soloists were Aquiles Machado and William Alvarado. On this occasion, the choir and orchestra was entirely Colombian, with the exception of a few Venezuelan musicians residing in Colombia who contributed their voices and their experience with the work from the choir and the orchestra.

What difficulties and / or virtues did you find this time?

The difficulties come from the complexity of a new work for the orchestra and the choir. In this case a work with rhythmic complexities, with a dense orchestration, full of drama and interpretative subtleties typical of the character and structure of Arvelo Torrealba's poetic text .

What you call "virtues" occurred in the excellent work of the orchestra and choir. Two most gratifying “surprises” were: 1) The young spirit of the two participating university choirs, very well prepared by Maestras Diana Cifuentes and Ana Paulina Álvarez. In the two choral rehearsals with piano I was able to work on nuances, dynamics, character, diction and interpretive elements of the Cantata. There was a lot of empathy with the young singers, a very nice work indeed.

2) The excellent response of the orchestra. OSNC is an excellent, dynamic, lively and disciplined orchestral ensemble. I think there was identification with the work, and the work of a week was done with the necessary efficiency. I was able to distribute the time of the rehearsals with comfort. I realized upon arrival that most of orchestra principals had solved the complicated passages. The whole program was difficult and new for them, but my initial concern dissipated in the first rehearsal, when I verified what my son Carlos Izcaray, a regular guest of the OSNC, answered me when I asked him about the number of rehearsals available for that show: “Don't worry, Dad. That orchestra works very well, has a good level and will respond to you. You’ll be fine ”.

How long did you have to put it together?

1 week. 2 rehearsals with the choir, 5 rehearsals with the orchestra, from which 3 were together with the choir. The tenor was in 3 rehearsals, and the baritone only for the dress rehearsal, because his flight was delayed and couldn't make it for the 4th rehearsal.

What aspects should be considered when performing this work abroad? (Soloists, key instruments, choir work, on reading and the rhythmic work of the ensemble)

It is essential to have a good choir. Those times of Antonio Estévez when preparing a choir for months to reach the required level has already passed, or at least it should have passed. With the “Cantata Criolla” it happens that sometimes you only want to count on the enthusiasm of choral singers who have never sung major works, and that makes the work much harder. Today we have choirs of people who have, at least, listened to a lot of music, and who play music at least discreetly. Without underestimating the work of the beginning choirs, one must stand in the fact that the Cantata is a work of magnitude, difficult, and for that reason it is necessary to be demanding.

Regarding the orchestra, a good professional level orchestra in any country or region can handle this work. You do need a pair of Venezuelan maracas or similar ones, the little ones, not the big tropical ones like those from Los Panchos. The other requirement is that the conductor knows the score well in order to solve in advance the spots that need special attention in rehearsals.

I understand that this is not the first time that you and Juan Tomás Martínez (baritone singing El Diablo) work together. Does it make it easier the fact that both soloists have been Venezuelan and also have experience with the work?

As Maestro Sojo would have said in a single word: “Excellent”. I have nothing more to add.

How was this experience compared to that first time in 1987?

Well, that of 1987 was a storm of emotions. It was my first time, the presence of Maestro Estévez in the hall was intimidating. Nowadays, after having conducted it so many times, the tension that everything goes well is still present, but the fear disappeared a long time ago.

We know now that you knew the piece prior to the 1987 version. In fact, I understand that you acted as a choir conductor in some of the previous performances of this work.

In fact, I sang in the choir and conducted several of the choral groups for the 1977 montage, starting with the Caracas Chamber Choir. I was then one of Estevez's choral assistants.

What was your impression the first time you heard “Cantata Criolla”? How old were you then? In what context did you first hear it and how did it mark you?

In 1965, when I was a 15-year-old teenager and a member of the Orfeón Carora, the newly founded Casa de la Cultura de Carora invited Maestro Estévez to a conference on “Cantata Criolla”. I remember that talk in great detail. For us there was an artistic link between Orfeón Lamas and Maestro Sojo, (including my father as founder), Orfeón UCV with Estévez, (who was Sojo's student) and finally our Orfeón Carora conducted by Juan Martínez Herrera (Estévez's student at the University and father of Juan Tomás). Estévez described the work to us in great detail and played a recording. There were 35 minutes of bristling skin, the vision and hearing of a work worthy of Olympus. I had never seen a live symphony, so I was literally pierced by those sounds. Estévez became an unreachable sage for me. I never imagined that he would become my teacher and friend, and that he would entrust me to conduct the work that he cherished most and guarded in a golden chest. I am a privileged person, definitely.

How did your initial impression evolve until that first performance in 1987?

When I moved to Caracas in 1966, I entered the University Choir conducted by Vinicio Adames, and combined my studies in Sociology with musical experience. I entered the Lamas Music School, met and related to great Maestros such as Sojo, Castellanos, Carreño, Lauro, Moleiro…. Being the son of Eduardo Izcaray opened many doors for me. Estévez lived in France, but came to conduct the choir in his 25 year anniversary in 1968-69. The idea of redoing Cantata Criolla was always in the air.

But it wasn't until 1977 that it was reassembled. Singing “Cantata Criolla” with Estevez on the podium was an experience out of this world. He was a conductor full of energy and drive. I made mental notes of his gestures and demands. He directed it for the last time in 1983, for Bolívar's Bicentennial. At the end of that concert, when we were leaving the (Theater) Teresa Carreño, he told me "Well, kiddo, now it's your turn." In 1987 the Caracas Municipal Symphony Orchestra wanted to invite him to conduct the work again, and he declined that invitation and gave them instructions that I be invited with all his trust.

How has your perception of the work evolved since then, throughout all the times you have been in charge of this score?

I have simply reaffirmed my conviction that it is a monumental work, in keeping with the epic poem that inspires it, a magnificent representation of the confrontation of good and evil, of the dark with the luminous, of the telluric with the sublime and divine. It is not a party, it is a colossal drama with a happy ending.

Do you have a memorable version worth to mention?

Obviously that of 1987, both the Teresa Carreño (Theater) and the Aula Magna 2 days later, due to the emotional charge of having Estévez very pleased and euphoric in the room. The one of the Aula Magna of the UCV in 2008 with Simón Bolívar was tremendous. The one in Paris in 1995, at the Sorbonne, where we had to repeat the second part, and of course, the recent one in Bogotá had a very high level. Tenor soloist Cristo Vassilaco also rose to the occasion.

Could you tell us about the process of being chosen by Antonio Estévez to succeed him on the podium and recreate this piece?

Estevez honored me with his personal affection, but also with his trust and respect for my work. He said that I identified very well with his music. Once I conducted his "Canción de la Molinera" wih the Orfeón Universitario, and to my surprise he got on stage and told the audience "This kid has big spurs". For such a demanding and critical guy, a gesture like that was unheard of.

What was the most relevant teaching after putting together “Cantata Criolla” with Antonio Estévez as guide? (Text-music relationship. Technical aspects: balance, rhythm, ensemble, tuning, articulation, diction, expression.)

All that, everything. Imagine being able to learn yourself and then conduct the Brahms German Requiem with Brahms himself by the side.

In what way did Antonio Estévez participate in the rehearsals of that 1987 version?

He was present from the first rehearsal with the choir, alongside the pianist, but I must say that he let me work quite at my ease, and that the few interruptions in rehearsals were brief, respectful and appropriate. Thank God, he liked my work, and that is evident in the video when he goes up on stage excited, bathed in tears by the emotion.

“Cantata Criolla” continues to be the most representative work, the largest and the longest-running in the Venezuelan symphonic-choral repertoire. It has been performed numerous times, it has been recorded and today there are already many versions of it.

How do you conceive and position this work in the perspective of current Venezuelan, Latin American and universal context?

It is one of the greatest successes of symphonic-choral literature. It is the integral identification of a creator with a poem, with his country and with his people. I have witnessed how it was received in Europe, and now in Colombia. The "Cantata Criolla" is already a universal work.

I imagine that there must be a big amount of details to take into account, but principally, what elements and aspects would you urge to be rescued, respected and / or preserved in later versions?

I would suggest going back to the roots, to the original version of Antonio Estévez, which is what I have done. Respect the syntax of the text, the notes written as they are, the tempi in the joropo, place the instruments in their original set up, and use the original part of the maracas, the one written by Antonio. Not only is it excellent writing, but it is a must.

Is there any relevant aspect that you would like to add about Alberto Arvelo Torrealba's poem and its relationship with the music of Maestro Estévez?

I would suggest reading the open letter that the poet Arvelo addressed to Estévez and that was published in El Universal. Everything is explained in great detail there.

https://www.venezuelasinfonica.com/carta-abierta-de-alberto-arvelo-torrealba-a-antonio-estevez

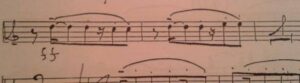

Finally, what do these two measures mean to you?

Those are two measures of the 1st clarinet part in B flat, measure 366 of the 2nd part. The actual notes are C, B flat, and D. In a rehearsal in 1977, the exact rhythm did not come out right on the 2nd violins, and Antonio would exclaim "Do-do, Co-ño… do-do, Co-ño".

I confess that I had already heard the anecdote with this extract, which caused me a lot of sympathy to find while we rehearsed the “Cantata Criolla”. But it is definitely much funnier when told by someone I know who experienced it first hand, so I couldn't resist the urge to "ask".

Thank you very much for your willingness and time for this interview, dear Maestro, which I hope will contribute to preserving our historical, cultural and musical heritage. Hopefully fate conspires so that you will soon be invited to conduct "Cantata Criolla" in other latitudes and again in Caracas. I express in advance my desire to be able to be part of that show. In this interview we confirm that you are also an ambassador of this transcendental work and we can trust that its reception in other lands will always be a revelation.

The last question is reserved for the readers of this article.

Who do you prefer: Florentino or El Diablo?

Links of interest

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dc0CwCe0yyw

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=63umItXGRLM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kmn9DolPOp8

Photos courtesy of Felipe Izcaray (Archives of the National Symphony Orchestra of Colombia)